I’ve been thinking a lot about cancer lately. It’s not the most fun topic, admittedly, but that hasn’t stopped my ruminations. Cancer is characterized by the cells from one part of the body growing uncontrollably and, sometimes, spreading to other areas. The uncontrolled growth leads to tumors. It can lead to death in the worst cases. And it can leave people scarred, physically and emotionally, if they do survive. The same is true for the people in their communities, friend groups, and families.

Like most people, cancer has touched my family multiple times. I lost my Tia to metastatic ovarian cancer in 2020, which I’ve written about before. In 2023, I lost my father-in-law to pancreatic cancer. There have been others. Uncles. Other aunts. Cousins. Neighbors. Friends. Some have also passed, but thankfully, many others have survived and are in remission.

According to the American Cancer Society’s most recent report, “Cancer Facts & Figures 2025,” this is far from unique. The report states, “More than 18 million Americans with a history of invasive cancer were alive on January 1, 2022, most of whom were diagnosed many years ago…” (ACS 2025). Furthermore, “…over 2 million new cancer cases are expected to be diagnosed in the US in 2025 and more than 618,000 people will die from the disease” (ACS 2025). While treatments have changed and improved, the ripples of those diagnoses and deaths will still be felt in 2025 and years to come.

I know it’s a coping mechanism that I’ve been thinking about cancer a lot. I can logically understand that it’s a way to deal with grief that still affords some level of distance. I don’t need to feel when I can instead think about it incessantly. Still, I like to think my obsession is proof of my devotion. If I didn’t feel my grief deeply, if I didn’t care, I wouldn’t be compelled to reach out in this way. To learn. To write. It’s the story that I tell myself. So I’ve not just been researching cancer, but I’ve also been consuming a lot of content about it.

First, there were the medical shows. This included a brief foray into Something’s Killing Me, a program that highlights very rare disorders that are life-threatening and often misdiagnosed. At first, I thought it might be good to know about lesser-known health issues. Ultimately, I had to put that one down because it fed into my health anxiety too much.

Next were podcasts and shows like Scamanda and Anatomy of Lies, respectively. They highlighted two high-profile cases of women who lied about cancer diagnoses and used those fake diagnoses to profit. One was a church going mom whose community poured money, time, and care into her while they were lied to. The other was a writer for Grey’s Anatomy who used her cancer, as well as the trauma of those closest to her, to fuel her career by writing about it for television.

And then there was Belle Gibson. She was an Australian wellness influencer who had a meteoric rise after starting an app called The Whole Pantry. The app was meant to have shopping lists as well as healthy recipes that were still accessible for the average person to make. But the real draw behind the app was Gibson herself. According to her, the recipes and her app’s purpose were inspired by her own experience with terminal brain cancer. She told the internet that she had been curing herself not with chemotherapy or radiation but with the power of nutrition. While given six weeks to live, four months tops, she was alive four years later, made whole in her kitchen and looking healthier than ever.

Brain cancer is one of the most notoriously aggressive forms of cancer. This is due to many factors. For one, brain cancer grows in a more finger-like shape, with tendrils that seem to be reaching out to spread into other parts of the brain. This makes an already difficult place to operate, due to the delicate and interconnected nature of our brains, even more difficult. To cut the cancer out would risk too much in many cases. Again, according to the ACS, of the 24,820 people who are likely to be diagnosed with a brain cancer or other nervous system cancer, 18,330 of them will die (2025). That’s about 74%.

These facts are what, ironically, made Belle Gibson’s story even more awe-inspiring. Rather than the knowledge of the severity of brain cancer making people more skeptical about Belle’s claims, many chose hope. While their hope may have been misplaced, it’s clear that they were people reaching for something.

What I find so fascinating about this story isn’t Belle herself. Many people have lied. Many more have gotten rich off it. My fascination lies in how she represents the complex interplay between capitalism, wellness culture, startup culture, conspiracy theories, science denialism, and the medical industrial complex. And as somebody deeply invested in feminist science & technology studies, it checks all my boxes.

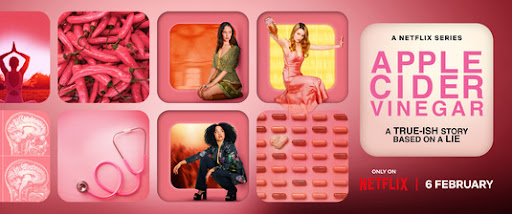

So I was primed and ready for a show like Netflix’s Apple Cider Vinegar, created by Samantha Strauss. The show takes the story of Belle Gibson, as well as the story of another popular Australian writer and wellness influencer, Jessica Aingscough, and dramatizes them to create a series that is thoughtful, smart, funny, and at times genuinely heartbreaking.

The show is, in a nutshell, about a healthy woman pretending that she’s sick (Belle played by Kaitlyn Dever), a sick woman pretending that she’s well (Milla played by Alycia Debnam-Carey), and another sick woman actually grappling with the complexity of being sick (Lucy played by Tilda Cobham-Hervey). The story is also propelled by the character of Chanelle, based partially on one of Belle’s former friends who helped expose her, played by Aisha Dee.

Apple Cider Vinegar represents a refreshing and, dare I say, feminist mobilization of fiction in a post-truth world. Most of us on the left have some understanding that we have become increasingly polarized as a society, partially through the internet, which has become a major source of misinformation and radicalization against science, against each other. The show is aware of this. So rather than do a cut-and-dry retelling of Belle’s story, it leans into the meta nature of parasocial relationships, the absurdity of social media and wellness spaces, and how technology and capitalism enable and disable connection and misinformation. It leans into spaces of confusion and ambivalence. It invites you to do research in a way that is still entertaining. When I finished the show, I immediately started to read more about Gibson, needing to know which parts were narrative inventions and which were true. Indeed, the series ends with what would be the typical text telling you what became of Belle after the events outlined in the show. But then the text cuts out and Belle pops into frame to say, “You know what? You can Google it.” And you should. That next part is maybe even wilder.

To this end, every episode has some variation of a disclaimer somewhere towards the beginning: “This is a true story based on a lie. Some names have been changed to protect the innocent. Belle Gibson has not been paid for the recreation of her story.” It’s always spoken by one of our actors as their character, to the camera, addressing the audience directly. They know it’s fake. They highlight to the viewer that this is fake to make sure we know it. Just like Belle knew her cancer was fake. In another instance, the disclaimer is accompanied by a bit of monologue that comes up against the question of truth, fiction, and reality explicitly. In that scene, Hek, a PR person hired by Belle to help fix her reputation, says:

“This is a true-ish story based on a lie. Some names have been changed and characters invented. Which is…Do you care? Should you? Fake news. Post-truth. Our arrogance where we fuck facts and cherry pick science we want to believe in….Stories were meant to connect us. But our compulsion to narrativize and dramatize heroes’ journeys, goodies, baddies. We’ve become incapable of objective thought.”

Some might write this off as ham-fisted, but it explicitly names the ongoing culture of science denial and fake news, which has only strengthened since Belle Gibson was exposed in 2015. The battle for reality is still being waged and is more intense than ever before. Fact-checking is rendered useless in the face of people (many of whom are lawmakers) who gleefully proclaim that their detractors spew fake news or leftist propaganda. Which then helps to create the heroes and villains in neat little boxes. What I personally see happening is that facts are rendered meaningless in a space where affect is the key currency of capital. If reality has been dissolved, it is through feelings and the monetization of feelings that we enable its dissolution.

Make no mistake, this is fundamentally linked to capitalism. Which makes it so jarring to hear Apple Cider Vinegar play a clip of a younger Mark Zuckerberg saying:

“The web isn’t going to solve disease or solve poverty. But what it does is it makes it so that people can share information more effectively and know what’s going on. When people are better informed, then people can make better decisions.”

We often say that when you know better, you do better. But in a post-truth world, that’s not the case. Furthermore, it’s an idealistic sentiment that I’m not sure people like Zuckerberg ever really believed. If they had, wouldn’t there have been better protections in place to prevent misinformation from spreading at an earlier juncture? But it is a useful lie based on some element of truth. It’s a good story. And it could have been true. It could have been that way, but that path just wasn’t as profitable. It is far more profitable to monetize emotional modulation, to turn our reactions into a form of labor that sustains their companies while it helps to tear us apart as communities and societies.

And this is not something that is just a problem with somebody like Zuckerberg or Facebook. This is a fundamental issue with the tech-bro startup culture that is increasingly interwoven into all aspects of our lives. The show makes it clear when it talks to a young photographer scammed by Gibson in the Netflix dramatization. When asked why he worked with Belle, even though he wasn’t sure that she was for real, he says:

“Yeah, but you believe in it, and it becomes real. That’s how perception works. That’s how startups work. Like, I’m doing some work on this hypnosis app at the moment. Man, the results are fucking unreal. You got some spare cash to invest?”

The diagloue’s emphasis on the interrelationship between belief and reality fits wonderfully with the larger themes of lies and truth that are part of Gibson’s story. But the invocation of startup culture reminds us how much these big startups are built on selling products that don’t exist yet. They often gain funding by selling a story, a feeling. And when he cheekily asks the journalists interviewing to invest, he shows that he’s telling a story because it stands to benefit him, to profit him.

It’s hard to think of Belle and not be reminded of Elizabeth Holmes. Her company Theranos is disastrous proof of how this startup ethos can be when brought into the space of health and wellness. Holmes sold a story about kinder, gentler ways of taking blood because she was solving a problem that many people have. So she sold a story about how it could work, knowing that many experts told her it wasn’t likely to work. She pushed forward, wanting to prove everyone wrong. She thought she could make it real. So she dismissed naysayers, even when they were concerned members of her own company. And she got her and her company huge press by telling a story over and over about the prevention of grief, of pain. Holmes frequently said that she wanted to build a world where fewer people to have to say goodbye to loved ones too soon. She was selling hope. Storytelling is a part of being human, and because of that, it’s become an increasingly important part of selling products, as a clip of Bill Gates says on Apple Cider Vinegar itself.

It’s the same impulse that’s discussed in Karen Hao’s Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman’s OpenAI. The book does an excellent job of showing the costs of AI at every level while also keying in on how the story OpenAI has told has shifted based on the needs of the company and its profit motives. But the idea that endless growth is not only possible but necessary for corporations is a pervasive one that is extractive and dangerous. As Milla says in one episode, “Instagram is ugly and fake and uncontrolled growth. You know what does that? Cancer cells.” The push to maintain profit margin enables the spreading reach of data centers, which gives OpenAI the compute and energy to push for integrating AI in every aspect of our daily lives as products, even without proper safety protocols. Under capitalism, uncontrolled growth abounds in the most dangerous of places.

But the wildest part of the show is that even as it’s dramatized, it’s drawing on so much unbelievable truth. While there are characters that have been blended and certain moments added, so much of the story is taken directly from the reporting done by journalists Beau Donelly and Nick Toscano in their book The Woman Who Fooled the World: Belle Gibson’s Cancer Con. They helped to expose her lie, and their in-depth reporting in the book is recreated often throughout the show.

In fact, many of the moments that seem designed to drum up both ire and empathy for Belle Gibson, such that they couldn’t possibly be real, actually are, according to their reporting. The moment she faked a seizure at her son’s birthday party, her making a scene at the funeral of Jessica Ainscough by loudly sobbing despite not having known her well, Belle’s mother’s own health problems and willingness to bend the truth, the school of thought that claims juicing and coffee enemas can cure cancer, and that pink turtleneck in the infamous interview Gibson did with Australian journalist Tara Brown are all real. The dramatizations instead work to put her actions in context and try to piece together her motivations. But even then, they’re based on an understanding of how she acted with many people who knew her intimately. It’s a cliche for a reason: sometimes truth really is stranger than fiction.

And again, it’s the meta nature of the show’s framing that best enables its impact. In one scene, Milla, after having been diagnosed with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, a rare and aggressive form of skin cancer, is meeting with her care team. While they advise amputation as the best chance to extend her life, Milla tells them that she’s not sure this is the right course of action after spending some time Googling amputation, which then led to Googling alternative cancer treatments. Instead, Milla proposes mistletoe therapy, much to her doctor’s chagrin. After she cites a real scientist (Rudolf Steiner), we move to a black and white clip of an actor playing him and explaining his hypothesis of why mistletoe would work against cancer, taken straight from literature on him. The scene then shifts back to the meeting room, where her doctor denounces mistletoe therapy as “Total quackery,” countering her with information about the adverse effects and reactions. Still, Milla persists. She is unwilling to do the amputation. She wants another option. The clip pokes fun at the idea of mistletoe therapy, something I thought was a joke until I started researching. Milla’s refusal to do chemotherapy, is inspired by her reaching for hope in that parasitic plant.

Milla’s reaction is, of course, shaped by the world she lives in. They emphasize that she is a former party girl working in the magazine industry, a space where beauty is emphasized and valued above all else. While it’s not fair to assume that it was only vanity that would shape one’s decision to deny amputation, we cannot dismiss it as having no impact. An ableist society sees people with different bodies as less than or damaged, which contributes to a society where the loss of a limb is felt by some as worse than death. And it is in a desperate situation where your life may change significantly or you may die, that people are willing to turn to alternative medicine.

And it’s also ableism that informed Belle’s real-life unwillingness to get mental health care before her cancer lies began. Donelly and Toscano note that doctors had indicated that her migraines and other symptoms she complained of were not the result of any structural abnormality in the brain, as an MRI proved, but likely the result of the stress and anxiety of being a new mother. Belle resisted the idea that she needed psychiatric help, which could have been a useful intervention that prevented her from spreading misinformation that put the lives of really ill people at risk. It’s in this way that Milla and Belle’s plights are connected by a refusal to accept what is happening to them, shaped by historical and ongoing stigma around mental and physical illness, especially for women.

It cannot be ignored that women often have their health concerns dismissed by healthcare providers. This is a truth that serves to sow distrust of doctors and also pushes people towards alternative medicine. And yet it also cannot be ignored that white women like Milla, and Belle especially (as a blonde, thin, and “normatively attractive”) have far more privilege than Black women, Indigenous women, Latinas, and Asian women in these realms. Systemic medical racism also serves to sow distrust of doctors and pushes people towards alternative medicine. This brings to mind the ongoing phenomenon of conspirituality, where people in new age and wellness spaces are particularly susceptible to being radicalized towards conspiracy thinking, especially in the context of health and science. (If you’re looking for a useful primer that maps these spaces, check out the podcast by that very name, Conspirituality.)

The so-called Hirsch Institute on the show, based on the real-life Gerson therapy, is one clear example with its juice cleanses and coffee enemas. But another is more subtle. In one scene, Milla talks with Arlo, a former classmate whom she reconnects with and eventually dates before her death. After seeing a person at a retreat they’re attending who had gotten an amputation and survived cancer, Arlo turns to Milla.

Arlo: “Must be inspiring. The energy in the group?”

Milla: “You think?”

Arlo: “Yeah, survivor’s energy. It’s nothing more powerful.”

Milla: “It’s toxic. Sick energy. You know they did it to themselves, right? I did. I knew I was putting all this shit into my body.”

Arlo: “The chemo…”

Milla: “No, not the chemo, before. School, uni, I just worked so hard, and I thought, I don’t know, it was my right to get fucked up on a Wednesday if I felt like it. But I knew.”

The exchange taps into conspirituality because of how Milla plays into anti-science new age beliefs that all health issues are manifestations of our actions and emotions, and we can change our actions and emotions to cure ourselves. Milla decides that her illness is in her control. It is penance and punishment for partying, drinking too much, not eating properly, and not getting enough sleep. But this self-blame serves a purpose: it affords a level of agency to think that we’re the cause of the problem. That we could have avoided it. Because it’s harder to think that sometimes, terrible things happen, no matter how hard we try to stop them. And it gives us a path to healing: I didn’t listen to my body then, but I can listen to it now, and in doing so, I can heal despite what the doctors say. Conspiracy theories proliferate because of the emotional purposes they serve. They offer comfort through certainty in a chaotic and unknowable world. They are stories that can enable us to buy juice cleanses and special salves, just like those mobilized by start-ups, but with a different coat of paint.

And we are more susceptible to these ways of thinking when we do not have community. It is in the absence of familial care and community that Belle chooses to brute force her way into finding connection in online spaces by falsifying her health status. On the show, she is stood up at her own baby shower, and then turns to online mommy blog forums to spin a tale about brain cancer. It is because of this post that random women on the forum reach out to her, offering support and encouragement. Belle is enveloped on screen by floating words and emojis, a feeling of relief on her face as she soaks up not just the attention but the care. It’s also there that she learns about Milla and her wellness blog, their stories starting to intersect, and giving Belle raw material to help her shape the false story of survival that she builds an empire on.

And Gibson’s real life empire was vast and built through tech. She honed her storytelling about her health on online forums. She got in on Instagram and amassed a huge following with her story once she nailed it down. She decided to build an app to enable herself to be in the pockets of people around the world, after building a less successful website. Her app was successful enough that she was one of the developers solicited to create app integration for the first Apple Watch. She idolized people like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, and made herself a darling of the tech crowd, which further legitimized her to the people around her and further enabled her to lie and profit from that lie.

Ultimately, I think Apple Cider Vinegar is a story about care and computing:

- What and who do we care about as a society? What do we value, and what paths does it lead us down?

- How does capitalism and the ethos of the tech world and startup culture bleed into our everyday lives?

- How do we come to feel close to others by virtue of their online personas, and how is this a function of the lack of community that exists in our everyday lives?

- How do we find solace in lies when reality feels too harsh?

These are how I articulate the core questions of the show, because they’re questions that animate my work and that I feel are more important than ever as we continue to puzzle through the interrelationship between how technology changes our world in both beautiful and terrible ways. I don’t think the creators of network communication, the many scientists who helped make all the nuts and bolts that come together to make the internet, could have imagined Instagram, or The Whole Pantry, or Apple watches, or a show like Apple Cider Vinegar and the real story that inspired it.

But the more that we can bring together tech and tenderness, care and computing, the more we can anticipate problems like these and work to solve them. Not with comforting lies and simple stories, but with nuanced and clear-eyed understanding and evaluation of the facts.

As I think about cancer, I keep coming back to Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals. It is the both/and I believe we need. It weaves together individual and society, personal and political, with humor and fear and strength and complexity. The character of Lucy seems to best represent that in this show. When Lucy says, “I like my chemo with a bit of magic,” it makes me think of Lorde in the best way. A sense of spirituality can still exist alongside working with science. A critique of the medical industry can exist alongside valuing innovations that can and do save lives.

The vision of Black feminist thought, especially through Hip-Hop Feminism, is best embodied in Joan Morgan’s push for us to be “brave enough to fuck with the grays.” To me, that means we think critically. We listen to the story and think about its purpose. What am I being sold? How does this story benefit me or not? We ask these questions even when the truth feels too complex or painful.

Chemotherapy doesn’t always work, but that doesn’t mean it never works. Nutrition cannot cure brain cancer, but good nutrition is supportive for people struggling with illness, and access to healthy, good food should be a right. We can do everything “right” and still we can get sick. The internet brings us together while it also pushes us apart. We need the nuance if we want to really understand how things work. We need the grays if we want to be part of making a more just world.

Like I said, I’ve been thinking about cancer for a while. And I think I’m going to be thinking about these questions for a while. I hope you will, too.

Leave a comment